Why are these summer books indebted to an Austrian author for nihilistic rants?

On the bookshelf

Hot Thomas Bernhard Summer

If you purchase linked books from our site, The Times may earn a commission of Librairie.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

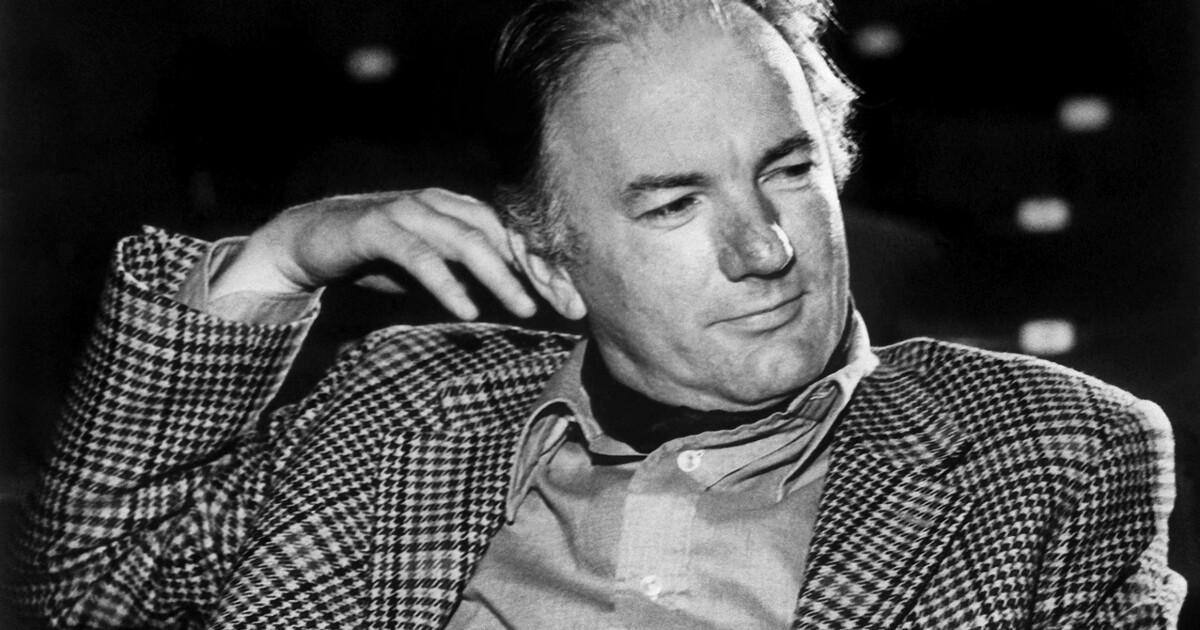

Thomas Bernhard’s name appears in the dust jacket copy and preprint reviews of three novels coming out this summer, and that’s no coincidence. “In the Berhardian universe”, declares a jacket; “told by the love child of Thomas Bernhard and Lydia Davis,” reads another. An early review of the third calls it a “direct approximation to the style associated with the Austrian writer Thomas Bernhard”.

It’s a weird selling point, even more so in our attention deficit age. Bernhard was a monologue fueled by forceful misanthropy, disgust and vitriol. Sentences last for pages. The narrators of his novels usually describe the fate of a close friend who, after working on an art business for years, recently ended it all. Bernhard, disgusted by his native country’s hypocrisy and complicity in the Holocaust, died in 1989 at age 58; his will prohibited the staging of his plays or the publication of his work in Austria.

Despite its “difficulty” in the text and in life, we find ourselves in Bernhard’s summer. Jordan Castro’s first novel, “Novelist, published two weeks ago, not only mentions Bernhard on its jacket, but also refers to one of his books in the text. Mark Haber’s second novel, “Chasm of Saint Sebastian”, released last month, is the closest thing to a simple tribute. Emily Hall’s debut, “The long cut‘, also published in May, follows an artist who wonders “what was my job” on a winding walk to visit a gallery owner.

Each of the three books could be described as a Bernhardian diatribe, or in some cases a diatribe, centered on the creation and purpose of art. Imbued with long monologues, emphatic hatred and distaste for modern life, they implicitly pay homage to a writer whose influence only seems to grow over the decades.

Bernhard himself would have hated a survey of its effect on contemporary fiction. Thanks to many Twitter accounts that daily post of quotes from Bernhard, I remember him writing, “I hated literary theories more than anything in my life, but above all I hated so-called theories about the novel.

Its closest modern-day adherents share some of this aversion to the bland, condescending formulas taught in many graduate writing programs. “I had just come out of an MFA program and I really felt like ‘this is what you have to do,'” Hall told me from his home in Queens, New York.

So Hall looked for other ideas. “I was bored to death,” she recalls. “I was at the Three Lives bookstore in New York, and I picked Bernhard’s ‘Concrete’ off a table. ‘Good,’ I thought, ‘the guy with no breaks.’ But when I read it, I realized all the things I thought were my faults – the digression, the self-contradiction – in Bernhard who has been writing. I became very excited.

Bernhard’s vogue probably dates back to the early 2000s, when Viking reissued a number of his books, attracting interest from English-speaking readers, particularly in his latest novel “The Loser”. Although his 13 novels have all been published in English, there is still much untranslated material among his countless plays, novels, stories and memoirs. In October, Seagull Press will publish “The rest is slander», a collection of five previously untranslated stories.

Years later, Hall was so inspired by her work that she tried to learn German. “I wonder what gets lost in translation,” she said.

Her admiration drew her into a cohort of like-minded writers. Hall spoke of the influence of Jen Craig, who is often compared to Bernhard. Reached by video in Australia, Craig said following Bernhard means learning to break the rules.

“It gives you the plot on the front page,” Craig said. “Once that’s settled, you can write everything else, anything that can’t be described by a plot.” Craig is the author of “Since the Accident” and “Panthers and the Museum of Fire.” “Since the Accident” is out of print, and “Panthers” was published by a small press, so Craig’s work is shamefully under the radar. I discovered “Panthers” in my local bookstore on the staff recommendation shelf. The little note under the book said “for fans of Thomas Bernhard”.

“At first, I was a bit embarrassed that there was a connection between me and this obscure, possibly misogynistic, over-the-top writer,” Craig said, about the frequent comparisons to Bernard. “But now I don’t care. I’m happy. For me, Bernhard is above all a realist. I don’t think many consider him a realist, but coming out of graduate school, the idea of writing was largely about theme, plot, and content. This stuff is so fake. The rantings… that’s the reality for me.

Because Bernhard’s style is so unique to him, I wondered if being associated with him was stressful for these writers.

“One of the things I’m interested in is dispelling the myth of spontaneous creation,” Castro said. “We learn by imitation, and we have this myth of the self-taught artist. I always wear my influences on the proverbial sleeve…. There’s a part in my book where the narrator says you learn the guitar by playing other people’s songs.

Castro’s book is about a novelist who sits down to write and does anything but. Eventually, launching into a diatribe about an enemy prompts him to write, “I suddenly felt a surge of uplifting energy…I could write a novel where I’m just talking about s—Eric; I could write my own version of [Bernhard’s] ‘Lumberjacks.’

Castro’s novel is the only one of Berhard’s books this summer that explicitly mentions the author, but all bear his imprint even though they vary widely in subject and tone. Haber’s “The Abyss of San Sebastian” is told by a man on his way to visit his friend and colleague Schmidt on his deathbed; both made their careers obsessed with a single work by a fictional syphilitic painter, Count Hugo Beckenbauer.

“The style, the myopic phrases: I realized I could use them to tell the stories I wanted to tell,” Haber said, speaking from Houston’s Brazos bookstore, where he’s the operations manager.. “His ghost is still there, but I don’t think I will already surrender to the quality of his sentences. I like to think my books are dumber; I don’t think Bernhard would write holy donkey.

Many other writers have been compared to Bernhard or have spoken of his influence on their work, including Mauro Javier Cárdenas, Claudia Piñeiro and the late Rafael Chirbes. But Bernhard’s influence, although broad, is still somewhat secret. For fun, I entered “The Loser” by Bernhard on the generator website, “What Should I Read Next?” The answer was rather Bernhard.

Maybe it’s a good thing we haven’t overemphasized Bernhard’s boom yet. The prospect of his style being too widely (and inevitably badly) imitated is grotesque. “How far and how far does it go?” Hall asked. “Is Bernhard’s style becoming a staple of the MFA?

This summer’s writers learned from Bernhard’s unforgiving approach to plot and what the novel can be without losing their own voice in the process; it’s a much better legacy than a flotilla of junky copycats. “Influences are a series of permissions,” Craig said.

“I felt relief when I realized Bernhard was still writing about the same thing,” Hall said. “There’s always this idea that you have to do something different with each book, reinvent the wheel.” Craig said something similar: popular novels are now more about Something: a period or a historical figure: “Today, as a novelist, you have to become an expert rather than a writer.”

The four writers were delighted to have the opportunity to talk not only about their work but also about Bernhard’s; our conversations sounded like the tail end of an Irish wake. Haber and I reveled in the abundant contradictions within even a single sentence of Bernhard. His novel pays homage to this in the letter Schmidt sends his friend, reading the nine pages of “his relatively terse email”.

Castro and I laughed at the episode of Schopenhauer’s dog in “Concrete,” a passage so funny we had to interrupt our partners’ bedtime routines to read it to them. “There’s such joy there,” Castro said. “It’s not being downright pessimistic.”

This seems to be the key to understanding Bernhard: not his depression but his joy. “He wrote, ‘Everything is ridiculous when you think about death,'” Hall said. “If you start there, everything is funny.” The warmth of annihilation is not lost on Haber either. “To write you have to have a certain hope, otherwise why would you write? There are dark ideas in Bernhard, but his writing is energetic and invigorating. It comes from a place of deep affection.

Above all, this particular culture of summer readings is Bernhardian in its focus on the struggle to create art, which for the artist is an existential question. “I thought I was choking on the mistake of believing literature was my hope,” Bernhard writes in “My Prizes: An Accounting.” This suffocation is prolific. But the heart of this statement is what makes his work, for all its nihilism, continually galvanizing in himself and his acolytes.

Ferri’s most recent book is “Silent Cities: New York.”