The author observes Charlie Brown through the decades

Studies of popular culture in America — books, movies, TV sitcoms, and even comic books — can range from the absurd to the truly insightful.

Some theorists will tell you that a romance novel is as important and beautiful as “King Lear”. Who are you to judge?

On the other hand, pop culture can tell us about ourselves in ways that serious dramas, movies, literary fiction, etc. cannot, or at least not in such an easily accessible way. Pop culture generally mirrors mainstream culture, but it can certainly reinforce certain cultural data and, if bold or provocative, help shape cultural mores.

The Western, for example, exemplifies the American myth of rugged self-reliance and, sadly, shows the Native American as savage.

MORE NOBLE DONATION: Mental Illness Meets Manipulation, Ends in Murder in a True Crime Book

Horatio Alger’s novels exemplify the “rags to riches” theme in American life, what we often call “the American dream,” but close examination shows us that persistent hard work alone is not enough. to generate a way out of poverty.

The poor boy in “Ragged Dick” or “Mark, the Match Boy” must show real virtue under pressure: return a found wallet or rescue the girl from the wheels of a runaway car. Then, because the girl’s father owns the bank, little Mark or Dick has the opportunity to work hard and rise.

Blake Scott Ball, educated at the University of Alabama and now assistant professor of history at Huntingdon College, has done a painstaking and graceful job of showing how the “Peanuts” comic generally reflected the changing issues and concerns of the American company and only on rare occasions stood out slightly.

“Peanuts” was America’s favorite comic strip. At its peak, there were 100 million readers every day.

Charles Schulz drew it for almost 50 years, through the relatively complacent but anxious 1950s of the Cold War, the tumultuous 1960s, the Vietnam War, the civil rights movement and the rise of feminism.

Ball starts by establishing Schulz’s own baseline. Shultz, we learn, served in World War II and became a staff sergeant in charge of a machine gun squad.

He saw fighting and came back realizing there was nothing glorious about war. Ever a believer, after the war he was born again and became a member of God’s Church.

Patriotism and faith would be at its core, and “Peanuts” would never be avant-garde, radical or progressive.

It wasn’t Shultz’s way or Charlie Brown’s way. The tape would be deliberately intermediate, ambiguous, like Charlie Brown himself, tasteless, but always open to a certain interpretation.

At first, for example, Linus’ security blanket and Charlie’s worried outlook were understood by some to be manifestations of existential alienation and cultural angst.

Later, “Peanuts” would become more Christian, with Linus quoting the Bible and some discussion/debate about the Great Pumpkin and even Santa Claus.

In 1968, Shulz incorporated “Peanuts” into young Franklin, although he was concerned that he would offend African Americans with this portrayal and it was unclear what role Franklin was to play.

During the Vietnam War, Snoopy, repeatedly piloting his doghouse into battle against the frustrated, never-successful Red Baron, became something of a mascot in Vietnam. American planes carried the image of Snoopy.

Schulz, like many of his generation, was conflicted about the war, but could never condemn it and remained determined to support the troops sent by the government to fight it.

Feminism was also a double-edged sword for Schulz. The right to abortion and even birth control were a problem for him. Obviously, they weren’t dealt with directly in “Peanuts.”

He endorsed traditional gender roles but also wished to promote gender equality. Lucy was tough and energetic, but ultimately the girls were portrayed with stereotypical female characteristics, nagging and not skilled enough at certain games, and rightly unhappy that society values beauty over ability.

I was particularly interested in Schulz’s maneuvers around environmental issues. Yes, he agreed our air, water and soil were degrading, but in “Peanuts” he seemed to exonerate capitalism and promote individual responsibility: we should turn off lights and recycle bottles, throw straws away plastic and ignore the gigantic chimneys that fill up. the sky with poison.

Over time, as America became more divided, Schulz became too conservative and “Peanuts” lost popularity to bands like “Doonesbury”.

The middle shrunk, the Americans took sides and left the ambivalent Charles Schulz and the bland Charlie Brown with nowhere to stand.

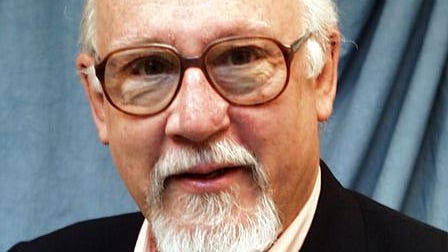

Don Noble’s latest book is Alabama Noir, a collection of original stories by Winston Groom, Ace Atkins, Carolyn Haines, Brad Watson and eleven other Alabama authors.

“Charlie Brown’s America: People’s ‘Peanuts’ Politics”

Author: Blake Scott Ball

Publisher: Oxford University Press, New York, 2021

Price: $34.95 (hardcover)

Pages: 239