The author delves into his parents’ revolutionary past, from Berkeley to Iran

On the promise of the failure of the revolution for his parents

Airplanes returning to Iran [after the revolution were] filled with these young idealistic militants who had worked for this revolution for so long. One of the stories people told me was that the people who filled these planes were singing revolutionary hymns. Both the leftists and, of course, the Islamists, who were also part of this revolutionary fervor.

At first, this leftist student movement group joined with the Ayatollah and the Islamic wing in an attempt to overthrow the Shah. It was really a coalition movement. It was a pragmatic choice, you might say. As soon as the goal [of deposing the Shah] was reached, then questions were raised like, ‘How do we govern?’ ‘Who will rule?’ “Who takes over? It became clear that the revolution was not going to turn out as the students had certainly hoped, or as my parents had hoped.

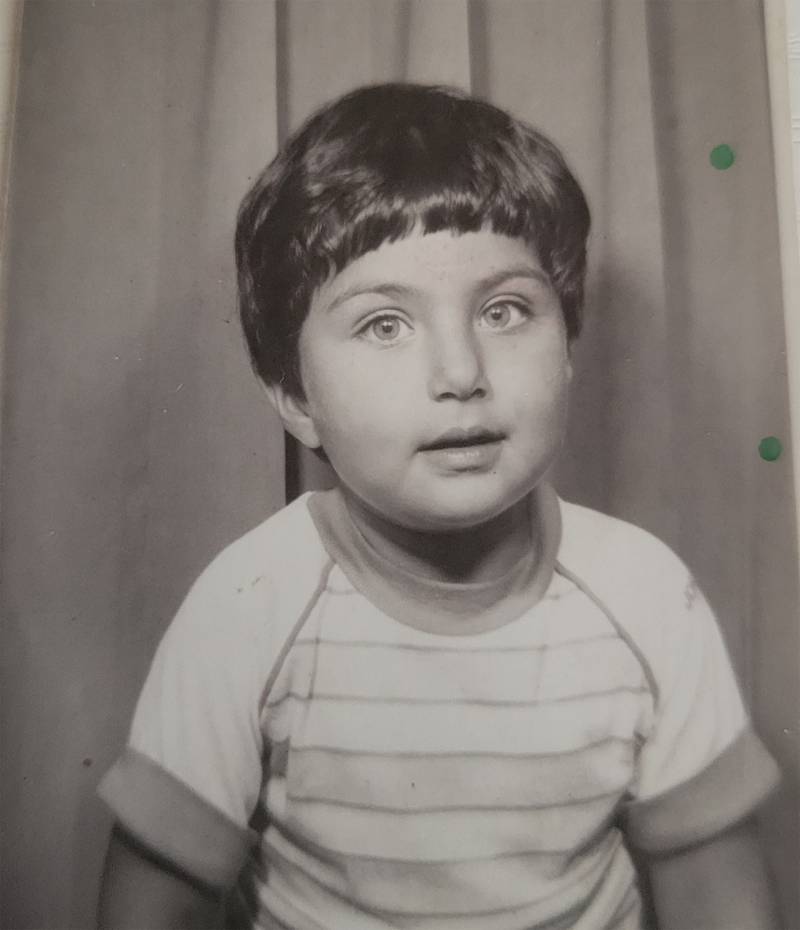

On his terrible escape from Iran on horseback as a toddler

I have very vague memories of Iran. I remember feeling part of a family. My mother was heavily pregnant with my brother when we escaped. When you’re a child and you’re pre-verbal, it’s like all of your memories are trapped in your body in some way, along with feelings or sensations.

I remember almost nothing of the trip. I remember wanting my mother that night. I remember when she told me I couldn’t be with her, I was confused and wondered if I was in trouble. I did not understand that there was not enough room for me on his horse. I didn’t understand that she was too big, the horse too small and the track too dangerous.

Now I also wonder if the last thing my mother would have wanted at that time wasn’t a child held tight to her. To be strong for me, she needed space for me. I was given my own horse and my own mustachioed smuggler. He scared me […]

It grew later still. The horse was rocking under me. I fell asleep against the ferryman. In my sleep, my fingers loosen their grip on my windbreaker. I woke up when it fell from my hand, floating down the side of the mountain. I begged the smugglers, my mother, my aunts and my uncle to stop the horses and go back to him. My setter went back and tried, but he didn’t see it.

I know where it is, I told him. I can find it.

But it was dark and late. We had to keep moving. The moment they stopped looking for my jacket, I filled myself with such deep fear that the rest of me crumbled away.

The world is unfair and I am carried away. I clearly remember that feeling.

Trying to find out who his father was, after he was executed by the Ayatollah in 1983

[In reporting this book,] people would give me these kind of little crumbs of [who] my father [was]. He bit part of his hand when he thought, or he clicked a pen when he spoke, or his voice when he laughed, or how he responded when he got angry. Suddenly there was a texture to him that he had missed before. Someone even recently sent me a photo of my dad laughing. I had never seen a photo of him laughing before. The only image I’ve ever seen of my dad speaking was in his lawsuit, which I found online.

So that’s how I was able to turn it from an idea into something more textured, more human and flawed, and quite beautiful. When I thought about it, I realized that this is actually how we get to know who people are. We have the impression of knowing the fullness of it. I started working on this book after my mother passed away. So there was a lot of comfort in feeling able to spend time with my dad.

Hearing a Storycorps interview with his mother, three years after his death from cancer

I was a bit frozen in place. I hadn’t heard my mother’s voice in so many years by then, and she and I were very close. All of a sudden, it was actually a very beautiful time to be a parent. She just showed me that she had seen me grow all these years. When I thought no one understood, my mom saw what was going on, how lost I felt, how much I cried for my dad, and how hard I tried to make sense of everything.

The way I took that moment was that it had given me space all these years, to take my time and find my way through this story and make my own peace with it.

On what she hopes this story will mean for her son one day

I hope this is where my son can go when he needs his mom. I wanted to be able to be with him. Whenever he needs me. You know, I started writing this book several years before he was born, so I didn’t start this project with him in mind. After it was born, it changed what the project meant to me. I hope my son will have something to hold on to after I’m gone.

Neda Toloui-Semnani will speak with California Report Magazine’s Sasha Khokha during a free virtual chat with the Commonwealth Club on March 23.