Owl and Pussycat author Edward Lear has the sensible knack for capturing the moment in drawings | Edward Lear

HThese absurd verses and limericks have delighted generations of readers, with The Owl and the Pussycat among the most beloved poems in English literature, but Edward Lear wanted above all to be recognized as an oil painter of great subjects. Today, many sketches of landscapes he created during his extensive travels around the world are to be exhibited for the first time.

They are an extraordinary visual diary of a nomadic and shy man who led an isolated life partly to conceal his epilepsy – a condition that carried great social stigma in his day. He spent over 50 years traveling across Europe, the Middle East, India and beyond, creating thousands of sketches.

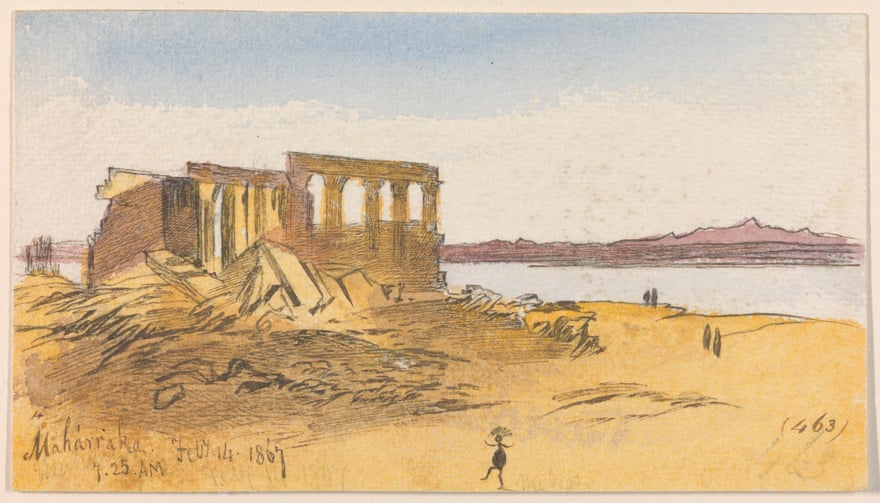

With extraordinary speed, Lear captured moments in time – noting the exact location, date and time of day in these images. Visiting the Temple of Amada, the ancient Egyptian temple in Nubia, in 1867, he drew it five times in 40 minutes, adding a timestamp to each: 6:50 a.m., 7:10 a.m., 7:20 a.m., 7:25 a.m., 7:30 a.m.

The series is one of more than 60 sketches by Lear that Birmingham’s Ikon Gallery will feature in what it describes as the first exhibition devoted solely to his landscape sketches. Entitled Edward Lear: Moment to Momentthe salon will open in September.

More than half of the sketches have never been seen before. Some have been matched with observations made by Lear in unpublished diaries he kept for several decades.

The exhibition is co-curated by Matthew Bevis, Professor of English Literature at Oxford University, and Ikon Director Jonathan Watkins.

Bevis told the Observer that Lear would be “shocked” to learn that his pictorial diary would be exhibited, as these sketches were essays for future works or memory aids for his travels.

Watkins compared them to “small time slots”: “There will be maybe a sequence of five or six: 5:20 p.m., 5:30 p.m., 6 p.m. He could just watch the light change or drift down a river. You have this sense of time passing and a sort of frantic desire to somehow capture it.

He added: “He often writes over the sketches, takes notes for himself. He returns to his hotel room or wherever he is staying and colors it. Sometimes he hears a song and he writes the musical notation. They are very revealing in a way that the most accomplished works are not.

Watkins singled out particularly “evocative” images of Lake Como and Malta as well as views of India, which he called “spectacular”.

Many of these sketches reflect the “absurd side” of Lear that he would not have included in his finished images, with details such as comic characters, nonsense words, and silly notes to himself.

Bevis said: “On the sketch he was writing various nonsense words. For ‘rocks’ it would be ‘rox’; for a “ravine”, more comically, he would write “raven”. He is a top notch verbal artist. The nonsensical words which begin to punctuate the sketches actually appear in a much more sustained way the year in which he publishes his book of nonsense – 1846. So there is a sort of surreptitious private joke going on.

Some sketches bear scribbles for himself: “A strong wind and so cold, I have to go back for a coat.” Others have notes such as “Semi Distinguished Tree”, apparently related to his nonsensical botanicals, and in an otherwise serious landscape he placed a cartoon-like stick man.

In 1858, after a six-day camel trek, Lear arrived in Petra and was “more amazed than I had ever been at any sight” – only to be chased away by local tribesmen. for trespassing on their land. He crunched the amphitheater in half an hour before escaping.

The exhibition draws on private and public collections in the UK and USA, including extensive holdings from the Houghton Library, Harvard, which few have examined.

Bevis said that Lear’s talent as an artist was eclipsed by his fame as a poet, and that although he “dreamed of becoming an oil painter of great subjects”, he rejected his own watercolors as less worthy: “But that wouldn’t be the first time Lear made mistakes. He sold the rights to his publisher of the absurd verse, which never went out of print, for £125 in the 1860s.”

He described Lear as “something of a sad clown” who endured terrible challenges and contradictions: “He was in debt when he died. Without any training, he produced what has now become one of the most beloved books of natural history illustrations of birds ever made – David Attenborough called him “the finest bird artist that ever existed. — and he was actually made the Queen’s Drawing Master. Victoria. So there is this strange mixture between a self-taught genius and difficult circumstances.

“He was born with chronic asthma. He was epileptic. He kept it a secret. He had a long history of depression. He had a series of unrequited relationships with young men. He therefore courted the upper echelons of society while feeling unworthy in many ways.

Bevis added that the value of his paintings exceeded anything Lear could have imagined: “He was always tough and would probably have offered a wry smile if he had known that one of his works would fetch nearly $1 million near 150 years later.

“But he is a great artist. You wouldn’t need to know anything about his nonsensical writings to find these sketches quite amazing.