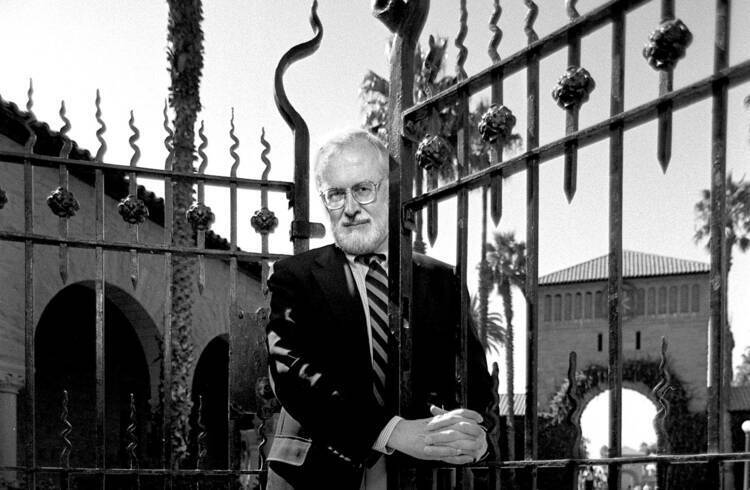

John L’Heureux: prolific novelist, former Jesuit and author of an alternative Eucharistic prayer

John L’Heureux, the prolific novelist, short story writer and poet, died three years ago this week in Palo Alto, Calif., at the age of 84. Famous for his novels (including Altamira Sanctuary, The Servant of Desire and The Medici Boyamong many others) and short stories appearing regularly in The New Yorker and The Atlantic Monthly, L’Heureux was a professor of English at Stanford University for 36 years and headed Stanford’s writing program for 11 years. Its alumni are among the best in the country. great novelists, poets and literary critics.

He was also for a time a Jesuit priest, although he has a quixotic history. He entered the Society of Jesus in 1954 (“I was the last generation whose classes were taught in Latin,” he once wrote) and quickly earned a reputation for literary talent, not always appreciated by his superiors. On his first day teaching in high school as a Jesuit scholastic, he told me in an email conversation in 2018, the community rector told him, “We are watching you. We know that you write poetry and publish it, and we have been warned about you. It was my first day of welcome to Fairfield Prep.

Excerpt from the Eucharistic prayer of John L’Heureux: “You have chosen us to be your children, you have called us to a life of joy and love; you gave us your beloved Son.

His first book of poetry, Quick as dandelionswas published in 1964 and was soon followed by two more collections of poems and a memoir, Picnic in Babylon. (Readers of a certain age may recall L’Heureux’s incomparable description of the famous Avery Dulles, SJ, tall and lanky, as “an incredible man: all bony and long, made of rake handles, brooms and old umbrellas”.) After ordination in 1966, he briefly studied for a doctorate in English at Harvard, but dropped out to become an editor at The Atlantic Monthly. “There I was, on the cover of Jesuit News, as a modern Jesuit who worked as an editor all week but took church calls on weekends,” he told me in 2018.” I was briefly acceptable.”

L’Heureux left the Jesuits and the priesthood in 1971. He remained prolific as a writer, although one newspaper in particular did not seem to care about his work. “When, after leaving the Jesuits, I started putting out a novel every year, I seem to remember America was there to let his readers know that my work was disappointing,” he told me. Nostra culpa, nostra culpa, nostra maxima culpaJohn.

But his memories of his time with the Jesuits, he told me, were mostly fond memories. “There are also the great men with whom I lived, including the provincial astrophysicist who saw me go out”, he recalls, “and the quiet saints with whom I lived for 17 years” .

When he died, America asked eminent novelist and short story writer Tobias Wolff, who had studied with L’Heureux at Stanford, to offer a reflection on his former teacher. This adaptation of Wolff’s introduction to Conversations with John L’Heureuxby Dikran Karagueuzian, published in America a week after L’Heureux’s death. “Reading his work, one can see, feel, the demands he places on himself for accuracy, essence, emotional honesty, aesthetic freshness, dig deep into the truths of our thoughts and desires. and present its findings without flinching,” Wolff wrote, “even—no, especially—when they challenge our conceptions of self and our certainties, and trouble the heart.”

“What were the paths that led him to this life, what surprises did he encounter along the way, what encouragement, what obstacles and distractions, disappointments and joys?”

“When you read a novel like An honorable profession or Altamira Sanctuarya short story like “The Anatomy of Bliss” or “Roman Ordinary”, you can’t help but wish you could sit down with the writer, ask him how he came to write such a work, how he came to to write,” Wolff wrote. “What were the paths that led him to this life, what surprises did he encounter along the way, what encouragement, what obstacles and distractions, disappointments and joys? has he learned from the art that he has practiced so well and for so long, and what has he learned from it?

One of the first publications of L’Heureux was somewhat forgotten in history: an experimental eucharistic prayer published in America in 1967. How it happened is a strange story, and one that requires some understanding of American Catholic culture in the 1960s.

After the bishops of the Second Vatican Council approved the liturgical constitution “Sacrosanctum Concilium”, theologians and liturgists of various linguistic groups around the world began to seek the best way to approach the concession allowing the use of the language vernacular at Mass. The Europeans led the way. , but English-speaking Americans were no slackers: a 1969 book edited by Robert F. Hoey, SJ, The Book of Experimental Liturgylists 36 new eucharistic prayers among its hundreds of new options for a liturgy in English.

In 1967, the Vatican gave the bishops of the United States permission to formulate new canons for the Mass in the vernacular. In response, America deputy editor CJ McNaspy, SJ, (if you refuse to believe that I didn’t invent a person named CJ McNaspy, SJ, your suspicions will not be allayed by this photo I found of him) asked two Jesuit writers to contribute Eucharistic prayers to the conversation. Rather than sound word-for-word translations of the Latin text, McNaspy and his friends were looking for “theologians with a gift of words and poets who know liturgical theology.” They found two in Donald Gelpi, SJ, and John L’Heureux, SJ, the latter having been ordained for only one year. America both published in its issue of May 27, 1967.

One of the first publications of L’Heureux was somewhat forgotten in history: an experimental eucharistic prayer published in America in 1967.

L’Heureux’s prayer would be recognizable to us today, but with certain inflections that allude both to his own theology and to the staging in which he lived. (This continuity was not always true; things got a little complicated at times in the late 1960s, liturgically speaking.)

In his Eucharistic canon, the emphasis on sin and atonement is toned down, with L’Heureux preferring phrases like “You have chosen us to be your children, you have called us to a life of joy and love; you gave us your beloved Son. Jesus, in the conception of L’Heureux, does not come to judge the living and the dead, but “to give justice to the living and to the dead on the day that you will fix”.

Later, his prayer asks that “before the eyes of all men, we live your gospel and be the sacrament of the presence of Christ, that we support each other in love, that our hearts are open to the poor , to the sick, to the undesirable, to all those in need. We pray that in this way we will truly be the Church of Jesus Christ, serving one another out of love for you.

It is a simple, no-nonsense prayer, devoid of the baroque prose and Cranmer-influenced phrasing of what was to come in the 1969 Latin Missal. But it is also a reflection of intense engagement with the joys and struggles of the world. A poet’s prayer, from the heart.

•••

In this space each week, America features literary reviews and commentary on a particular writer or group of writers (new and old; our archive spans over a century), as well as poetry and other offerings from America Media. We hope this gives us the opportunity to provide you with more in-depth coverage of our literary offerings. It also allows us to alert digital subscribers to some of our online content that does not appear in our newsletters.

Other Catholic Book Club columns

Good reading!

James T. Keane