In honor of World Mental Health Day, Gould Farm presents: Phyllis Vine, local author and mental health activist

Phyllis Vine, local author and mental health advocate, will speak at Gould Farm in Monterey on Friday, October 14; a book signing will follow. Photo courtesy of Hazel Thompson.

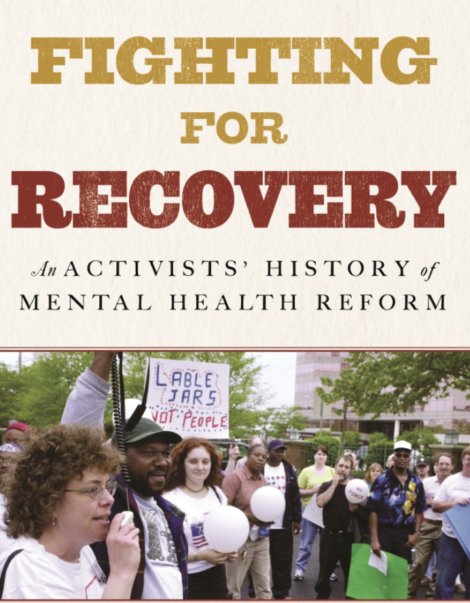

Monterrey— Phyllis Vine first broke the silence surrounding people with mental illnesses (and the families who care for and surround them) in her landmark 1982 book, “Families in Pain.” Over the next four decades, Vine has kept a close eye on the largely underserved and misunderstood mental health community, as evidenced by the vast and singular history of activist movements in said space, as chronicled in his recently published book. published, “Fighting for Recovery: A Story of Mental Health Reform Activists” (Beacon Press). At an auspicious time, as Monday, October 10 marks World Mental Health Day, the author will speak Friday evening, October 14 at 7 p.m. at Gould Farm; registration and live stream link available here.

Vine’s book focuses on how to build on the important work of individuals within the mental health community to benefit the many Americans whose lives have been impacted by a diagnosis of mental illness; her many hats – from historian and mental health activist to chair of the board of Gould Farm – converge in both researching and telling this story.

“Recovery may have revolutionized ideas about how best to help people with mental illness with transformed services, but the idea is just the beginning,” Vine writes. “And there was a pushback because not everyone agreed with the recommendations on the solutions. What they agreed on was what a mess the current mental health system is. Of the 10.4 million adults with serious mental illness in 2016, only 65% received mental health services. Up to 2/3 of people with psychotic disorders have waited six months or more to receive treatment services. Suicide, the tenth leading cause of death overall, is the leading cause of death among people aged 10 to 34. These are not recovery-oriented practices. Not even close.

Through interviews with key players, archival research and original reporting, Vine profiles individuals and organizations waging a medical and popular war of opinion from the mid-20th century to the early 21st. The activists Vine describes fought for the recognition that people with mental illness are individuals with the right to participate in their own journey of care; making recovery an accepted goal in a culture that saw people with mental illnesses as permanently “sick” with no hope of leading “normal” lives; and to reduce stigma, particularly because these diagnoses are often inaccurate, outdated and biased – principles that over time have led to demands for recovery-promoting treatments.

Throughout his book, Vine introduces readers to a wide range of colorful and complicated actors: Howie the Harp, a New York and Oakland-based activist who escaped from an institution as a teenager and co-founded the Mental Patient’s Liberation Front. ; Judi Chamberlain, a feminist involuntarily hospitalized in mental institutions who popularized the rallying cry “Nothing about us without us”; parenting activist Dan Weisburd, who campaigned for reform in California and spearheaded the creation of The Village treatment program in Long Beach; Laurie Flynn, the successful and energetic leader of the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI); and Philadelphia’s Paul Del Vecchio, a strong supporter of peer services who became the first consumer to work for the Federal Center for Mental Health Services, later becoming director of Addiction and Mental Health Services.

In the Berkshires, Gould Farm is a shining example of the potential for recovery that lies at the intersection of community life, meaningful work and clinical care. Founded in 1913, Gould Farm is the nation’s first residential therapeutic community dedicated to helping adults with mental health and related issues move towards recovery and independence through their practical and functional farm model. Beyond 413, World Mental Health Day marks an international day for global mental health education, awareness and advocacy against social stigma. It was first celebrated in 1992 at the initiative of the World Federation for Mental Health, a global mental health organization with members and contacts in more than 150 countries. Today, the overall goal remains to raise awareness and mobilize efforts for mental health issues around the world while providing all stakeholders working on mental health issues with the opportunity to speak about their work and of what remains to be done to improve mental health. health care a reality for people around the world.

Today, the fact that people with mental health problems can strive for recovery, have jobs, live independently and decide whether to take medication or pursue other therapies is due to activists and organizations Vine writes about. That said, she points out a sobering fact: these options aren’t available to everyone. People of color and those without financial means often do not have access to and suffer from programs that actually work, either in prison, on the streets, or in the other institutional settings that exist in the United States. Vine ends the book with a call to action: that we use the knowledge we have to dismantle programs built on faulty and outdated assumptions, and provide services where none exist.

REMARK: Phyllis Vine is an unequivocal pioneer in the world of mental health. She wrote the first book to discuss family relationships between people struggling with mental illness. Between 2007 and 2012, Vine edited MIWatch.org to aggregate mental illness news. She is currently Chair of the Board of Gould Farm, the oldest on-farm residential treatment program for people with mental illness in the United States. A former history professor at Sarah Lawrence College, she is also the author of “One Man’s Castle: Clarence Darrow in Defense of the American Dream” (2004). Learn more on its website.