Cancer ‘most likely a reaction’ to childhood trauma: Indonesian-Chinese author on guilt at being born a girl

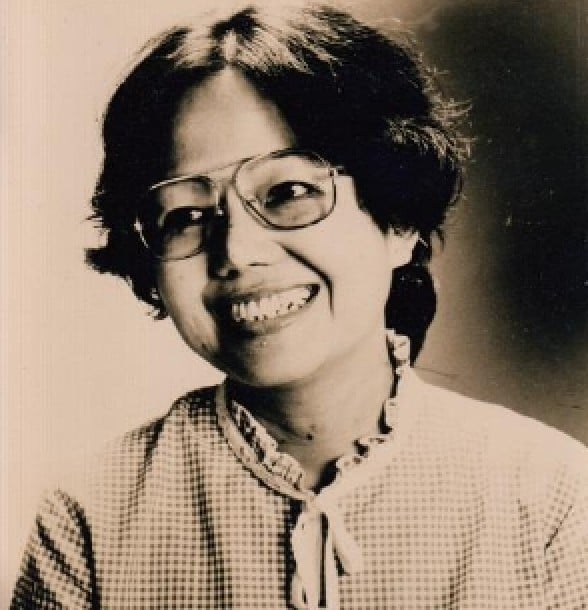

With a career spanning more than half a century, Indonesian-Chinese writer Marga T is one of the country’s most prolific authors.

Born in Jakarta to parents of Chinese descent in 1943, she showed an early gift for writing, with her first two novels, the romance titles Karmila and Badai Pasti Berlalu (The storm will surely pass ), being instant hits.

Of the 69 books she has published, her work has touched on science fiction, mystery tales, children’s stories, and dark chapters in history. The third volume of her Sekuntum Nozomi (A bud of hope ) tells the story of Chinese women raped during the 1998 riots in Indonesia.

But perhaps the most personal of all is his latest work, If only a poignant memoir “about the obligatory duty to have a son, and the tragic consequences for the family when no son is born”, she says This week in Asia in a rare interview.

In 1952, Marga’s mother died after giving birth to a sixth daughter. Marga was then only nine years old. Being the eldest, she carried the guilt of being born a girl, as her father expected to have a son so he could carry the family surname.

“I was accused of causing his death,” she said.

A few months after the funeral, Marga’s cousin slapped her with a sandal, dragged her by the hair, pinned her to the ground, beat her with a rattan stick and kicked her .

“I was violently beaten by a cousin without knowing why. My father did not come to my defense; didn’t even ask what happened,” she said.

Marga believes her cancer diagnosis in 1992 was “most likely a reaction” to her childhood trauma.

“(The doctor) said that unresolved childhood trauma between the ages of nine and 13 would suppress growth hormone, resulting in short stature. That’s me. It would also jeopardize the immune system and cause the cancer. It’s me too.

Work on If only was an act of catharsis, Marga said in the book, her first published in English.

It was written “in memory of my mother, not to shame my family, but to cleanse my soul, mind and body of bad childhood memories and their effects”. The names of family members mentioned in the book have been changed for privacy reasons, she said.

Marga’s fame is notable given that her rise took place during the reign of former dictator Suharto, who oppressed the Chinese ethnic community during his three decades of rule.

Among other regulations, he banned Chinese cultural manifestations and imposed laws that pressured Chinese citizens to adopt Indonesian-sounding names.

When he resigned in 1998 following massive nationwide protests, the country then transitioned to democracy and the Lunar New Year became one of Indonesia’s national holidays.

Marga says she was “not so much” affected as a writer during the days of Sukarno’s Old Order and Suharto’s New Order, as her work rarely touched on politics. “Teen romance books were considered harmless and did not attract the attention of the authorities.”

While Marga is part of a large community of Indonesian-Chinese writers – many more preceded her before the archipelago nation gained independence in 1945 – few have been well known.

“There have been many writers of Chinese descent in the past, but they are rarely discussed,” says Soe Tjen Marching, an Indonesian-Chinese author from the second-largest city of Surabaya.

“Many of these Chinese immigrants couldn’t write well in (their native language). They then learned the Malay language and started writing stories,” says Soe Tjen, who is also a lecturer in the Department of Language, Culture and Linguistics at the School of Oriental and African Studies at the University of London.

Nurni W. Wuryandari of the Chinese Studies Program in the Department of Literature at Universitas Indonesia wrote in a 2015 article that “Chinese-Indonesian authors and poets have produced works since the 1870s.”

“Their works were written in Malay as the lingua franca in the archipelago, which absorbed various elements from other languages such as Dutch, English and Mandarin,” she wrote in the journal. “Later, after the independence of Indonesia, elements of the standard Indonesian language were also incorporated into the works of these authors.”

Marga was seen by some as having distanced herself from her heritage due to her decision to publish under the name Marga T, who had hidden her Chinese identity from readers until some people unearthed her surname.

“The insinuation that T was from Tjoa really hurt me, like they know my life better than I do,” she said. This week in Asia .

“When I started writing, the name Marga T came to mind out of nowhere,” Marga said. “T is not an abbreviation.”

Yet his work continues to resonate with many in post-authoritarian Indonesia. Badai Pasti Berlalu was adapted into a new soap opera last year, and Karmila is currently being developed as another soap opera. Past adaptations of both titles have aired multiple times over the past few decades.

Hetih Rusli, director of IP licensing and digital publishing at PT Rekata Studio, a subsidiary of Indonesian media conglomerate Kompas Gramedia Group, said Marga T “paved the way for future female Chinese writers” in Indonesia and showed that “women have a voice that can be conveyed in written works”.

“Her female readers might be inspired (by the characters): ‘If a character in Marga T’s novel can be a doctor, I can be one too,'” says Hetih, who is working on the Indonesian translation of If only .

Charlotte Setijadi, an anthropologist who studies ethnic Chinese communities in Indonesia and an assistant professor of humanities at Singapore Management University, says: “For an ethnic Chinese woman in the New Order era to gain notoriety and popularity by writing stories relevant to Indonesian readers, regardless of ethnicity, was an important form of representation for Chinese-Indonesians at the time.

When asked how she wants to leave her mark, Marga replies that ethnic Chinese are “no different” from other Indonesians in their pursuits and aspirations, and that all citizens “should be able to find a way to live in harmony. next to each other”.

“We should try harder to accommodate each other and help each other to make Indonesia a prosperous and great country,” she said.

Meanwhile, Marga is working on a second memoir. As she noted towards the end of If only “This dissertation is a mission. I had been tortured physically and mentally during my growing up years, and this painful experience has been with me ever since.

“There’s only one way for me to get rid of it. By pouring the trauma on paper, I hoped to purge myself of it once and for all and share the experience with you in case you ever had to deal with such a thing.

This article was first published in South China Morning Post.