After finding it, the author parts with the 18th century painting looted by the Nazis from his family

Pauline Baer de Pérignon fought for a long time for the restitution of “Portrait of a Lady in Pomona”, painted by Nicolas de Largillière in 1714. The work belonged to Baer de Pérignon’s great-grandfather, the famous French art collector and patron Jules Strauss, who was forced by the Nazis to sell it for good less than its market value during the Holocaust.

After being held and displayed at Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden in Germany since October 1959, the 66.5-inch-tall portrait (framed) was finally delivered to Baer de Pérignon’s Paris apartment in January 2021.

Baer de Pérignon hung it at her home, but it has since been taken down and is to be auctioned by Sotheby’s in New York on January 27, with an estimated sale price of between $1 million and $1.5 million.

“I always knew that the painting did not belong to me. Jules Strauss has 18 living heirs and the painting is shared property. I couldn’t afford to buy the painting from others,” Baer de Pérignon explained in a recent interview with The Times of Israel.

Among the heirs is the cousin of Baer de Pérignon Andre Strauss, a professional art specialist who worked for many years at Sotheby’s. He casually mentioned to Baer de Pérignon in May 2014 that there was “something fishy” about the sale of some works by Jules Strauss, and that it “had been stolen”.

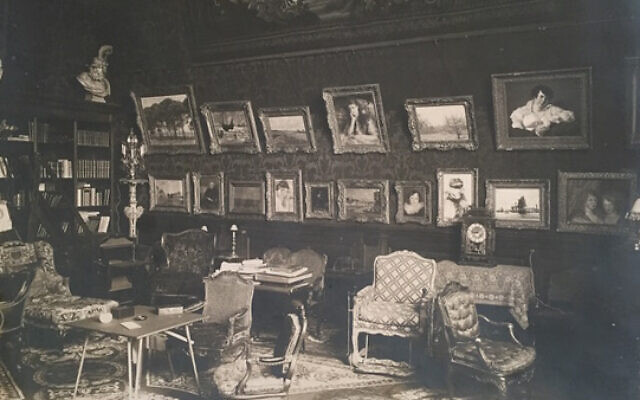

Strauss’s remark launched Baer de Pérignon on a years-long quest to figure out exactly which of the nearly 500 works of art in the collection of Frankfurt-born Jules Strauss were looted and what happened to them. The research, in turn, provided material for Baer de Pérignon’s best-selling book, “The Lost Collection.” It was published in French in 2020, and in English translation in January 2022.

Baer de Pérignon, who had co-written film scripts and hosted writing workshops, had no relevant knowledge or skills to embark on such a journey, but she was undeterred.

“The truth is, I was making it all up as I went. I started this research very hazy, looking at it from every possible angle. Really, my method was that I had no method”, writes Baer de Pérignon in his book.

She followed all leads and received instructions from various archivists, historians and specialists in the restitution of works of art looted by the Nazis. However, she did all the painstaking research herself.

“[Baer de Perignon’s] story is unique in that she undertakes a journey practically on her own, instead of hiring someone, and the details of which she knew next to nothing. She had little connection to art, but she learned about the process, from researching archives to putting together a restitution dossier,” said Ori Soltesprofessor at Georgetown University and co-founding director of Holocaust Art Restitution Project.

‘The Vanished Collection’ by Pauline Baer de Pérignon (New Vessel Press)

The main pieces of historical evidence uncovered by Baer de Pérignon were both helpful and puzzling. For example, information from auction catalogs sometimes conflicted with the list of looted works of art that Marie-Louise, Jules’s wife, compiled after the war, and with Jules’ own notebooks listing each work. of art that the “compulsive buyer” had ever acquired. (Baer de Pérignon borrowed the latter from his late cousin Michael Strausswho headed the modern and impressionist art department at Sotheby’s for decades.)

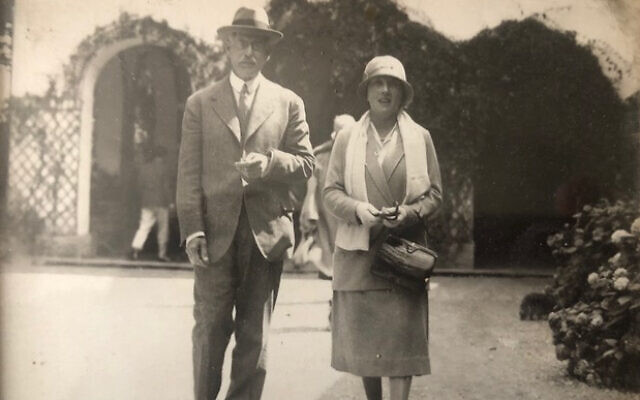

Despite Baer de Pérignon’s best efforts in her archival research and her interviews with elderly parents, she was unable to answer questions about how and why retired bankers Jules and Marie-Louise succeeded. to stay in Paris during the war, especially when their children and grandchildren fled to the free zone (“free zone”) in the south, and when so many Jews from the social and business circles of the Strausses were deported to concentration camps.

The Nazis even commandeered Jules and Marie-Louise’s apartment on Avenue Foch and drove them out, but Marie Louise was inexplicably able to return there after 1945 and live comfortably among many of her pre-war possessions. (Jules died of old age or natural causes in 1943.)

Jules and Marie-Louise Strauss (Courtesy of Pauline Baer de Pérignon)

Most frustrating of all for the author was his discovery that museums are far from eager to relinquish works of art, even when presented with solid records of evidence that they have been looted.

She was stunned when the director of the Dresden museum suggested to her that her great-grandfather would have been “happy to have sold his painting for a decent price”.

“Museums are interested in the provenance of art from an art historical perspective, but they are not interested in returning it to those from whom it was stolen. The burden of proof is on people like me, and it’s psychologically draining,” said Baer de Pérignon.

Jules Strauss’ office in his Paris apartment. (Courtesy of Pauline Baer de Pérignon)

“There is a lot of waiting. The process is vague and not at all transparent. You feel helpless because of all the bureaucracy,” she said.

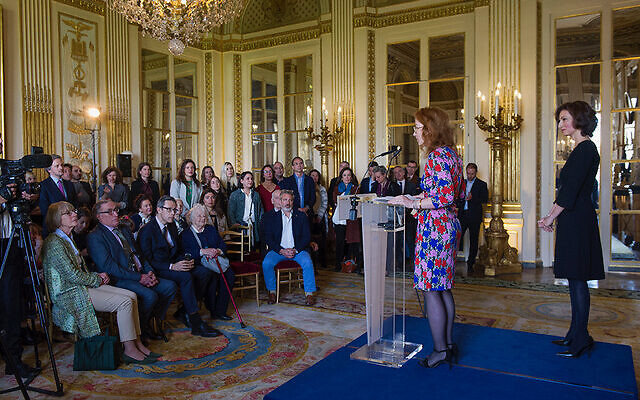

Baer de Pérignon was also able to find a drawing by the 18th century Italian artist Giovanni Battista Tiepolo which had been looted from Jules Strauss. It ended up in the Louvre’s collection after the war, and no one had thought of looking for its owner.

Baer de Pérignon found this ironic and infuriating, given that Jules Strauss had been a generous patron of the Louvre. Not only did he donate four paintings to the museum, but he also initiated the Louvre’s new framing policy in 1900, which associates paintings with frames from the time they were painted. Strauss donated around 60 frames for this project.

Pauline Baer de Pérignon speaks at the restitution ceremony for ‘Un berger’ by Giovanni Battista Tiepolo at the French Ministry of Culture, April 2017. (Courtesy)

The drawing was returned to the family in an April 2017 ceremony at the French Ministry of Culture, and it has since been sold.

According to Lucien Simmonsglobal head of restitution at Sotheby’s, the painting by Nicolas de Largillière returned to the Strauss heirs and auctioned on January 27 “is one of the most significant works by the artist ever offered at auction, comparable to other masterpieces -of the Artist’s Works Completed Around the Same Time.”

“The sitter of ‘Portrait of a Lady in Pomone’ has traditionally been identified as Marie Madeleine de La Vieuville, the Marquise de Parabère (1693-1755), who was the mistress of Philip II, Duke of Orléans when he was regent of France during the childhood reign of King Louis XV of France,” he added.

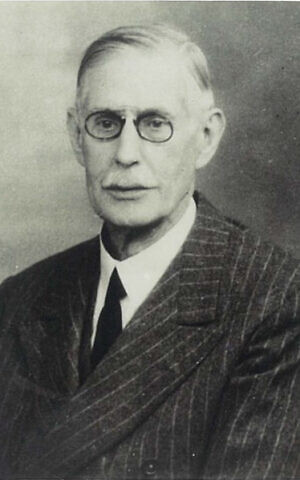

Jules Strauss before 1943. (Public domain via Wikimedia Commons)

Although Sotheby’s research and due diligence process has contributed to the restitution of hundreds of works of art over the past two decades since the establishment of its dedicated restitution department, the auction house does not is involved in this painting only after it has already been returned to its rightful owners. .

Nevertheless, “it is essential to honor and reclaim the history of these [Jewish] collectors and share their stories so that they become inseparable from the history of the works and are not forgotten. Each newly returned artwork is significant because it represents the culmination of a journey for the artwork and the family involved,” Simmons said.

Baer de Pérignon described the long and difficult restitution process as “a quest for identity”. It was more about trying to understand her late father (who died when she was 20) than the art itself.

“The book is really about him and what he didn’t tell me about my heritage. I’m more sad than upset,” Baer de Pérignon said.

Pauline Baer de Pérignon stands in front of ‘Portrait of a Lady in Pomone.’ (Courtesy)

Her father converted to Catholicism in his youth during the war and never spoke of his Jewish background. Baer de Pérignon had never known Jules Strauss’ legendary reputation as an art collector alongside other French Jewish collectors like Charles Ephrussi and Moïse de Camondo.

“I read testimonies of people rejecting the idea that they had been victims of spoliation… as a defense mechanism… Was it possible that we, the descendants of Jules, suffered from it? Strauss means ostrich in German – had we actively decided to stick our heads in the sand to avoid the truth? writes the author.

While identifying as a Catholic, Baer de Pérignon said this journey to restitution has helped her identify what has slipped away from her Jewish ancestry.

“I identify with the way Jews question things. I’ve always been like that,” she said.

Baer de Pérignon said she was sad to see “Portrait of a Lady in Pomone” fall from her wall after such a struggle to get her there. But even though she enjoyed gazing at her beauty, she always kept an eye on what was most important.

“Painting is not painting itself. It’s a matter of memory and justice,” she said.